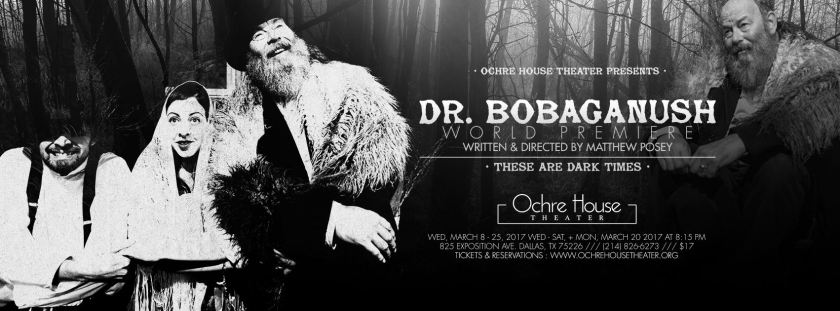

Dr. Bobaganush (The Ochre House)

Matthew Posey, genius behind The Ochre House, writer and director of most of their shows, has a unique gift for creating absurd, strange, shticky, profane, hilarious pieces with a cynical undercurrent. I say this with great admiration. Cynicism is often a powerful impetus for brilliant satire. Dr. Bobaganush is a bold, funny, fierce indictment of the holocaust and our current regime. As an elderly Jewish friend of mine once pointed out, the parallels are ugly and unsettling, and Posey has used his magnificent craft to stir us to the quick. You don’t know whether to weep or guffaw. It’s not difficult to watch until the very end.

Dr. Bobaganush (and his Carnival of Wonders) travels the European hinterlands with his family in a wagon, a mash-up of slapstick, prophesy and prestidigitation. Ochre House shows have a tendency to blend the comedic, oracular and grotesque and this one is no exception. The characters include Anne Frank and Mr. and Mrs. Van Daan. Anne is dressed to suggest Dorothy Gale of Frank Baum’s Wizard of Oz series. When she spends the night in Bobaganush’s wagon, his decrepit dad chases her sporting (what must be) an enormous erection. Ugh! Someone needs to put grandpa on a leash. For all the stuff and nonsense the doctor and his clan offer as entertainment, he undoubtedly has access to genuine psychic powers. While Anne and the Van Daans flee the Nazis, he senses something nefarious in the air. It’s obvious to the audience he’s on the right track, but at that time, no one could believe that such a ridiculous, unbalanced little megalomaniac could win such widespread advocacy, or wield such pervasive, toxic influence.

You never know what to expect when you visit The Ochre House, but it’s all to the good. For some reason, Posey’s bizarre combinations of the traumatic, banal, humorous and vaudevillian works inexplicably well, and no one who loves theatre should miss the opportunity to go.

Adding Machine: A Musical (Theatre 3)

From the outset, we can tell Adding Machine is not a conventional musical. A chorus of four supplies histrionic, operatic urgency and fills in by playing various roles throughout. Their often amusing behavior stands in stark contrast to the content of the lyrics. We begin with Zero and Mrs. Zero, climbing into bed, while the missus natters about gossip, social obligations, disappointments. Sadly, she is an unmitigated harridan, and it’s not long before she digs in: I was a fool to marry you, this sort of thing. There is a cartoony, excessive mien to all this, all the better to tickle you, my dear; a blending of social commentary and absurd humor. In the office we see the daily rhythm of adding numbers, and gradually catch on that despite their bickering, Zero and his assistant, Daisy DeVore, have an unacknowledged yearning for each other.

Rice was probably ahead of his time in writing this dystopian critique of the empty values behind capitalism. The subsequent score and libretto by Joshua Schmidt and Jason Loewith italicize and heighten the material. The murder of The Boss is merely a triggering event that propels Zero to death row, the afterlife, and subsequent examination of the foibles of humanity and need for purpose. There’s a wry undercurrent to the most serious of events, never letting us forget we are witnessing a marriage between the wretched and the ridiculous. Even when Zero is offered the opportunity to move past drudgery it would seem he is more devoted to his shackles. For all our encouragement to read him as a schlub, he is also an Everyman, finding his value as a person (and a man) in the soothing ritual of a repetitive job.

The Aliens (Stage West: Fort Worth)

Something about Annie Baker’s The Aliens suggests the spartan, arid, washed-out milieus of pieces like Altman’s Three Women, Bergman’s Persona or Rodrigues’ O Fantasma. Or perhaps the dry, taciturn boys of The Last Picture Show. Baker has fixed upon certain aspects of male culture, the sparse verbal exchanges, the intense demand for respect, the absence of extravagant feeling. The setting (N. Ryan McBride) for The Aliens, behind a restaurant where the waiters take their smoke breaks, feels hopeless and crumby: sand, butt buckets, metal chairs, trash, refuse and detritus. As if a haze of resignation has settled over everything. When Evan (a waiter) meets KJ and Jasper, he finds they’re hanging out because a friend (who no longer works there) has told them its OK. When they tell him they’re holding a Fourth of July party in this very same place, it’s a joke to us, but not to them.

Jasper is perhaps the post 21st Century version of the disaffected rebel poet. If anyone’s the alpha, it’s Jasper. KJ is the easy-going, affable stoner, and Evan the nervous nerd, gobsmacked that he’s found favor with the cool kids. When Jasper addresses him as “Little Man,” he’s not being snotty or dominant, he’s just being matter of fact. Like when men nickname the tall guy “Stretch.” Evan may be jittery and famished for belonging, but he has some sense of purpose. He’s intelligent and teaches at Orchestra Camp, even if the jazzy side of life (girls, catching a buzz, breaking laws) has eluded him. Nothing shakes KJ and Jasper, they have no place to be. Their only recourse to act as if they’re goofing and tossing because everything else bores them. What lifts The Aliens from the hungry squalor that engulfs our three buddies is the ease of mutual male affection. Unspoken and barely acknowledged. A man learns pretty early there are two kinds of guys in the world. The ones who want to be your friend and those who want to tear you apart. Or at least piss on you. Whatever their reasons Jasper and KJ have nothing to prove, and have no reason to disparage Evan. So they become his friend.

It may be nearly miraculous that Annie Baker has developed an ear for the way fringe-dwelling teenboys talk, and how they must scratch out an existence in a world that expects men to fall somewhere between troglodyte and rocket scientist. If you feel anything sad, if you’re cerebral or passive, you’re weak. There are times when men wanting to connect might as well be trying to build a bridge to the moon. With toothpicks. And somehow. Somehow. Annie Baker has cut through the aching, pervasive despair of these boys who need to be men, and distilled something startling and radiant from it. The awful pointlessness just keeps piling on, but Baker finds a key as fragile as origami (a guitar, a cigarette, a sparkler) and these lonely souls discover something exquisite. Something remarkable.

With the pitch-perfect, visionary direction of Dana Schultes, Joey Folsom, Parker Gray and Jake Buchanan give us performances that are strong, deeply touching and crisp. Folsom has just the right balance of insouciance and gravitas, Buchanan brings an introspective lightness, and Parker the insecurity and fear of exclusion all guys have felt. This script could have crumbled in the wrong hands, but Schultes and this astonishing cast have taken us deep into the thick of Baker’s Dystopian drama. The Aliens is a valentine for guys with no tools to care for anybody, much less one other, or themselves.

Boy Gets Girl (Resolute Theatre Project, L.I.P. Service and Proper Hijinx Productions)

Indoctrination and culture often go hand in glove. We pick up (often subtle) clues from the behavior of others, regarding attitudes towards men and women, boys and girls. Here in the 21st Century, we like to think we’ve evolved past ignorant, outdated assumptions, but sadly many persist. Ideas like male privilege, female helplessness, predatory dynamics, still manage to sift into our consciousness, so taken for granted they go undetected. Such is the case with Rebecca Gilman’s brilliant drama: Boy Gets Girl. Though the title might suggest a number of lighthearted romantic comedies, it also implies the woman has little choice in the matter. Her role is to be pursued and resist as long as she can. It leaves no room for refusal. At the outset, Teresa goes on a blind date with Tony. Their first beer together goes well enough, but the second time (when they meet for dinner) it’s clear they’re not a good fit. Tony mistakes her tact for ambivalence, and what might have been played for laughs, gradually becomes more and more disturbing. Before Boy Gets Girl finishes, Tony will subject Teresa to increasingly poisonous behavior, diminishing her life without even being in the same room.

I’m not sure Gilman’s aim is to point the finger towards men, as it might be to explore, and bring attention to our oversights and mistaken ideas. When men get together and compare notes on women their reasoning can lack enlightenment (to be kind) and to be fair, such conversations on the part of either gender can result in an us versus them mentality. It’s to Gilman’s credit that she drops intelligent, if indirect, hints throughout the script. Teresa must interview a cheesy movie maker (based on Russ Meyers?) who’s made a career of films that objectify women. Her male colleagues, Mercer and Howard, are unsettled to discover the code on her calendar is for keeping track of her period. This polarization, this conflation of the mysterious “other gender” with adversarial chemistry or dehumanization, goes to the core of Boy Gets Girl and cultural permission to take liberties. What happens on the stage, Gilman suggests, only begins to explain the hazardous complications of sexual attachment between men and women.

Five Women Wearing the Same Dress (MainStage Irving-Las Colinas )

Alan Ball’s Five Women Wearing the Same Dress (playing at The Dupree Theatre in The Irving Arts Center) is a splendid, engaging, intriguing comedy. Like the best comedies, it emerges from an actual narrative, as opposed to hanging gags on a tenuous skeleton. You might recognize the writer’s name from his association with American Beauty and Six Feet Under. Mr. Ball is an iconoclast, cheerfully mixing cynicism with a soft spot for frailty, and a lack of tolerance for pretentiousness. Five Women is set in the Knoxville, Tennessee, in the early 1990’s. The occasion is a wedding. The poster of Malcolm X hanging over Meredith’s bed (sister of the bride) sets the tone. The conversation takes place between five bridesmaids (Frances, Meredith, Tricia, Georgeann, and Mindy) none of whom, it seems, are especially close to the bride. Frances: frail, mousy, sweet, functions as defender of traditional morals (“I don’t drink, I’m a Christian.”) while Meredith leads the charge of transgression.

You wonder if Five Women was chosen for its timely consideration of paradigm shifts in America’s salient values. The women smoke pot, imbibe, discuss their sexual escapades, while Frances is definitely a buzzkill. Mindy is a lesbian. Meredith disparages the phoniness of the posh wedding, her sister, the ceremony, while Tricia questions the validity of marriage as an institution, and long term romantic relationships of any kind. The name of Johnny Valentine is brought up repeatedly, as the Pan-like dreamboat who’s bedded three of the women and flirted with all of them. What makes Five Women so enjoyable and effective is Alan Ball’s refusal to stoop to didacticism or pontificating. He avoids stereotypes and clichés. For all the “sinful”, indulgent behavior, none of the women seems particularly evil or noble, just normal and free to find their own path. Ball confides the underpinnings of their attitudes, and laces the story with enough pathos to make it genuine and resonant. His dialogue is so crisp and skillful that laughter is nearly a reflex.

Five Women Wearing the Same Dress is a refreshing, engaging show. Under the direction of Dennis Canright, the ensemble (Tammy Partanen, Nicole Neely, Liz J. Millea, Mandy Rausch, Laura Saladino and Hayden Evans) is nimble, sharp-witted and energetic. It closes this weekend, so don’t miss your opportunity to catch this great production.

Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune (L.I. P. Service Productions)

Terrence McNally’s Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune has (the more you think about it) a bizarre premise. Johnny and Frankie work in the same diner. Frankie is a waitress and Johnny is a cook. When Act One opens the two are “consummating” at the end of a date. Frankie sees this as casual (but not indiscriminate) sex. Johnny has decided that Frankie’s the woman he wants to spend the rest of his life with. Johnny believes in love at first sight. This, by itself, is not so awful, but Johnny comes on like a hurricane at a funeral. Like the old joke about the amorous Lesbian couple, Johnny doesn’t believe in second dates. He seems ready to move in. He’s charming and absolutely genuine, but his better qualities are soon engulfed by his utter lack of finesse. He does nothing by halves, but seems determined to tell Frankie how to behave as well. As any of us might imagine, this is a dubious approach to a new relationship.

McNally seems to be exploring role-reversal, too. Johnny is the romantic, emotional one, crazy to commit. Frankie is happy to take it slow, and see how things go, before jumping into an intense, lifelong attachment. It’s curious how Johnny seems to embody the downside of heartfelt passion. He seems to forget that Romeo and Juliet shared a mutual intensity. Johnny is so cocky and bossy (in addition to being tender and moonstruck) Frankie doesn’t know whether to appreciate his warmth or kick him out. He’s not just loopy, he seems to verge on being certifiable. As for Frankie, her sensible attitude is undercut by a pervasive sense of melancholy and spiritual damage. When she confides she sometimes pulls up a chair to watch an abusive couple across the courtyard, we wonder if she figures toxic attention is better than none at all.

So, then, this is where Terrence McNally takes us. Frankie isn’t just cautious, she’s swimming dark waters. Johnny believes in living for the moment, and that Frankie and he share a destiny. The plot does much to encourage this. Like most excellent playwrights McNally leaves us at the watering trough and lets us reach our own conclusions There’s something vaguely twisted (and strangely satisfying) about the painful, somber thread that winds through this entire piece. We all know that successful relationships are not about finding the perfect mate, but the perfect match. Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune teases us by sparking our longing for this pair of slapdash, tattered souls. We wind up feeling some odd mix of the frightening and sublime. We’re afraid they’ll stay together and afraid they won’t.

Grounded (Second Thought Theatre)

Written by George Brandt, Grounded, is a drama with one character, a female fighter pilot who is never named. She speaks to us directly, chipper and affable, combining the traits of warrior moxie and the simple determination of someone with a job to do. She has earned her place among other cracker- jack fliers, bonding at the local watering hole and enjoying the camaraderie. When a guy approaches who is neither intimidated nor alienated by her prowess, they connect and have sex that very night. Apart from being kindred spirits, they clearly have no use for traditional paradigms. After they marry, he’s happy to stay home and take care of their daughter, cook for her, and stoke the hearth fire for the long stretches when she must be away. Their sex life is spirited and nurturing.

By taking us along on her enigmatic odyssey, we begin to identify with the pilot. There is a categorical difference between wielding her gleaming, silver vessel and the enormous robot bird of prey. She begins to undergo a shift in attitude. A sea change. Her job and the psychology that make it possible begins to spill into her civilian time. She forgets to remove her uniform, the richness of familial love begins to dissipate. Her professional focus and unconditional purpose begin to waver.

Despite the possibility that Grounded is based on a true story, the significance of a woman pilot seems undeniable. The warm, lovely photograph of her (belly exposed) during pregnancy, her fear that her daughter’s obsession with “Pretty Pony” means that she’s a “hair-tosser,” the wife she sees running to the car of a target. As she gradually acquires destructive power, we cannot ignore the irony that she also brings life into the world. When this ordeal finally overtakes her, it’s difficult to know how it will resolve itself.

As “The Pilot”, Jenny Ledel handles the task of occupying the stage for 90 minutes with authority and finesse. Ledel is beguiling, convivial, subtle. Fierce and stoic when she needs to be. She accommodates this challenging, enervating role with such skill and implacable dedication. She will get under your skin and sneak into your dreams.

Miller, Mississippi (Dallas Theatre Center)

Miller, Mississippi opens in Jackson, Mississippi in 1960 around the time of The Freedom Riders and the civil rights movement in the Deep South. Siblings Thomas, John and Becky are listening to their African American housekeeper, Doris (Liz Mikel) tell about a decrepit, haunted house that wouldn’t burn down. They are interrupted by the sound of a gunshot, and mother Mildred appears, with blood on her evening gown. Their father has just shot himself. This sets the pattern: a decent, intelligent, quaint family from the deep South is gradually stripped of their pretensions.

Just like the rotting house in the ghost story, there is something vile going on in the Miller home.

Becky, John and Doris, in their own way (often in secret) try to rise above the complicity and depravity that thrives in their family and the world outside. Thus the Millers become a metaphor for the systemic, pervasive racism of the South. Terrible things are happening and most turn a blind eye. John, the most

naive and tender (even more so than his mother) believes that truth and goodness will prevail, while the phrase he hears repeatedly is: That’s just how things are. When Thomas is wailing on John and things escalate, John gets the upper hand by jabbing him in the shoulder with a fork. Instead of asking what would drive such a gentle soul to such extremes, they immediately ship him off to an asylum. This is indicative of the level of tacit collusion and sad resignation that infects the Millers and the culture they inhabit.

This theme of subordination to revered despots, and decadence beneath the veneer of civility can also be found in Dexter’s Paris Trout and McCuller’s Reflections in a Golden Eye. This is well-trod material, but playwright Boo Killebrew swings her trapeze over the volcano with precision and grace. (So does this remarkable cast.) The ugly is interwoven with the everyday, the unconscionable tolerated as the price of avoiding the terrifying march of progress. In the skillful hands of Killebrew, what might have become a cliché of Southern Gothic treachery is a measured, fierce, quietly devastating story of the poisoned spirit and sick of heart.

Paper Flowers (Kitchen Dog Theater)

I have often despaired of trying to express my unequivocal enthusiasm for theatre that is disturbing, harrowing, violating, and yet ferocious, powerful and brave. Theatre must often grapple with and articulate a world that (beneath the surface) is terrifying and grotesque. So when Kitchen Dog Theater (God bless them) engages with the contradictory needs between our raw humanity and what culture demands of us, I find the experience exhilarating, overwhelming, flamboyant and everything that fierce, defiant, contemporary theatre should and must be. There will (of course) always be room and need for pleasure-driven, blissfully ridiculous comedy, but certainly there is enjoyment to be found in even the bleakest of theatrical narratives. Theatre has an intuitive feel for turning emotion and struggle into extravagant, spectacular, though precise imagery and sacrament. Sometimes it helps to explore the frantic and abysmal, it makes the unknown less daunting. Excuse my indulgent use of adjectives as I seek to nail my experience with Egon Wolff’s Paper Flowers.

Eva, a sad, lonely, middle aged (but never pathetic) merchant who loves to paint helps a homeless, destitute guy by letting him carry her groceries. When he refuses remuneration she hastily tries to get rid of him, even when he pleads that there are men waiting to kill him. “Not my problem,” she replies, without seeming especially unkind. Perhaps I was not listening carefully, but somehow the guy turns it around, rather quickly, and she offers him food and temporary refuge. His actual name is Roberto, but he prefers the nickname his cronies gave him: “The Hake”. (A hake is a vicious reptile that is something like a cross between a piranha and a cottonmouth.) While he is eating his soup, he sets a He’s charismatic and subdued, but even before we see his behavior in her absence, something is unmistakably off about him.

Days after I watched Paper Flowers I found how utterly it had gotten under my skin. It is enormous in the sense that it drags us into a cluster of ideas in such a flagrant, chaotic, thorough and implacable way. The connection between Eva and Hake. Is it about romance, libido, genuine empathy, alms-giving, rage, pride? The bread of shame? Hake seems to keep mistaking sympathy for pity. But if Eva (in Hake’s view) couldn’t possibly appreciate his situation, than I suppose the borgeoise are incapable of anything but pity. Subsequently, Hake cannot accept anything offered out of love (genuine or not) he must take it by force. He makes a speech that amounts to this. We become so lost in what the other needs us to be, that we lose our identity. There is probably something to that.

Pippin (Firehouse Theatre)

Based on the life of Charlamagne’s oldest son, the musical Pippin hit the ground running, opening on Broadway in the 1970’s, directed by Bob Fosse and featuring Ben Vereen as the Ringmaster. Using a circus motif, the players converge to tell the story of Pippin, a prince who is hungry to taste everything the world has to offer, after getting high marks and a degree from the university. He explores war, religion, politics, monarchy, agrarian life; he assassinates his father and supplants him on the throne. His conniving step-mother plots to overthrow him for the sake of her son and the younger prince, Lewis. From the beginning the avid, jovial, acrobatic troupe promise a phenomenal, exciting finale that will knock us on our collective tuchas.

Pippin’s structure is odd, if intriguing, advancing the narrative with lots of gags and digressions, using ingenuity and vaudevillian nonsense (as well as juggling and other dazzling hi-jinks) to keep the story bouncing. Pippin is skinny and young, charming, deferential, the least glamorous of the cast. War teaches him how cheaply life can be forfeited, the church about corruption, the monarchy about the difficulties of responsibility. There’s a thread of merriment and whimsy informing this spectacle. Pippin has a conversation with decapitated soldier. His grandmother instructs him in the ways of hedonism, and leads us in a singalong. We are privy to the courtship between Catherine and Pippin, in which she wins him over at least as much by craft as charisma.

Derek Whitener, has a brilliant, intuitive feel for staging joyful, memorable shows. He makes these enterprises seem effortless and electrifying. Pippin is a warm, charming, saucy, experience, with gobs of dash and convivial energy. It’s touching and hilarious, wise and giddy. It sparks a spontaneous joie de vivre that puts any momentary cynicism to shame.

Silent Sky (WaterTower Theatre)

Written by Lauren Gunderson, Silent Sky was inspired by the life of American astronomer, Henrietta Leavitt. Born in the late 19th century, Henrietta Swan Leavitt graduated from Radcliffe, going on to take a position at The Harvard College Observatory. She joined “Pickering’s Harem” mischievously (if insensitively) named because it was all women. Considering the meticulous and precise nature of their work, their wages bordered on the criminal, even for the early 1900’s. Struggles with illness left Leavitt partially deaf, yet dedication and vision facilitated her genius, and discoveries that would forever change the science of ascertaining earth’s place in the heavens.

Gunderson opens Silent Sky contrasting Henrietta with her sister Mira, who finds more fulfillment in music and nurturing a family than pursuing astronomy and mathematics. This dialectic between the religious and secular, the spiritual and cerebral, continues throughout the narrative. The sisters sustain their strong attachment long after Henrietta has started her work at Harvard (menial at first). But the submersion necessary for intense research makes it difficult to maintain correspondence with Mira, or a blossoming romance with colleague Peter Shaw. Much of Silent Sky considers what Leavitt must have sacrificed to pursue and realize the implications and moment of what began as an inkling. An intuitive spark of insight.

I’ve never cared for words like “feminist,” because they seem reductive. The unjust attribution of Leavitt’s legacy (only alleviated posthumously) is without question. And her achievements were diminished because she happened to be female. This is a flaw in the transactions of humanity, the insecurity of a patriarchy already tilted to male advantage. “Henrietta Leavitt discovered the relation between the luminosity and the period of Cepheid variable stars.” Put another way, she realized we could gauge the distance between the earth and a particular star, by measuring its brightness. This turned astronomy on its head, but it would be a long time before she would receive the credit due her. This is not a question of politics but ethics.

What makes Silent Sky so effulgent and delightful is Gunderson’s masterful blend of the scientific with a dazzling grasp of the cosmos. We are immersed in Henrietta’s exquisite sense of wonder as she loses herself in the brilliance of endless galaxies. When she explains to Mira that the beauty of elegant theory and pattern of spheres and suns in motion amounts to her religion, we do believe her, but we also share in her ecstatic reverie.